WINGED WORDS WINDSDAY

Compiled by Rob Chappell (@RHCLambengolmo)

Vol. 2, No. 2: November 9, 2022

Welcome to Orion, the Warrior-Hero of the Night Sky!

Editor’s

Note

The constellation Orion the Hunter is rising in the

East by midevening now – one of the most prominent figures portrayed on the

sky’s dome by our distant ancestors. Probably modeled on Gilgamesh, the

legendary King of Uruk in Mesopotamia (early 3rd millennium BCE),

Orion is one of the most easily recognized constellations, appearing as a giant

warrior-hero in the night sky. Here are three classic poems (followed by an

article about Gilgamesh) to welcome Orion back into the evening sky.

The

constellation Orion the Hunter, as portrayed in Urania’s Mirror (1825) by

Sidney Hall. The bright blue star Rigel marks Orion’s left foot.

In Germanic mythology, Orion was known as Aurvandil,

and this name was especially applied to the star Rigel, which represented the

giant’s left big toe that had been frostbitten (hence its blue color) and cast

into the sky by the god Thor. In Old English, the name Aurvandil became

Ëarendel, a herald of hope in the frosty Yuletide season of the year:

“Ëala

Ëarendel, engla beorhtast,

ofer

middan-geard monnum sended.”

“Hail

Ëarendel, brightest of angels,

over

Middle-Earth to humankind sent.”

à

Cynewulf (Old English, 9th Century CE)

Orion

in Aratus’ Phaenomena (3rd Century BCE)

“Aslant beneath the

fore-body of the Bull is set the great Orion. Let none who pass him spread out

on high on a cloudless night imagine that, gazing on the heavens, one shall see

other stars more fair.”

“The

Winter Scene: Part II” by Bliss Carman (1861-1929)

Out

from the silent portal of the hours,

When

frosts are come and all the hosts put on.

Their

burnished gear to march across the night

And

o'er a darkened Earth in splendor shine,

Slowly

above the world Orion wheels

His

glittering square, while on the shadowy hill

And throbbing

like a sea-light through the dusk,

Great

Sirius rises in his flashing blue.

Lord

of the winter night, august and pure,

Returning

year on year untouched by time,

To

hearten faith with thine unfaltering fire,

There

are no hurts that beauty cannot ease,

No

ills that love cannot at last repair,

In the

victorious progress of the soul.

“Stars”

by Marjorie Lowry Christie Pickthall (1883-1922)

Now in

the West the slender Moon lies low,

And

now Orion glimmers through the trees,

Clearing

the Earth with even pace and slow,

And

now the stately-moving Pleiades,

In

that soft infinite darkness overhead

Hang

jewel-wise upon a silver thread.

And

all the lonelier stars that have their place,

Calm

lamps within the distant southern sky,

And

planet-dust upon the edge of space,

Look

down upon the fretful world, and I

Look

up to outer vastness unafraid

And

see the stars which sang when Earth was made.

“Winter

Stars” (1920)

By

Sara Teasdale (1884-1933)

I went

out at night alone;

The

young blood flowing beyond the sea

Seemed

to have drenched my spirit’s wings —

I bore

my sorrow heavily.

But

when I lifted up my head

From

shadows shaken on the snow,

I saw

Orion in the east

Burn

steadily as long ago.

From

windows in my father’s house,

Dreaming

my dreams on winter nights,

I

watched Orion as a girl

Above

another city’s lights.

Years

go, dreams go, and youth goes too,

The

world’s heart breaks beneath its wars,

All

things are changed, save in the east

The

faithful beauty of the stars.

“Leadership

Lessons from Gilgamesh, the World’s First Superhero” by Rob Chappell, M.A.

Adapted

& Expanded from Cursus Honorum VII: 4 (November 2006)

Read

an English translation of the Gilgamesh Epic @ https://www.jasoncolavito.com/epic-of-gilgamesh.html

and its epilogue at https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1813.htm.

The Gilgamesh Epic is the oldest extant

epic poem in world literature. Based on a series of Sumerian heroic poems from

the late third millennium BCE, the epic was compiled in Mesopotamia during the

18th century BCE in the Akkadian language. The plot of the epic revolves around

the adventures of Gilgamesh, an early King of the city-state of Uruk (reigned

ca. 27th century BCE). The compilers of the epic wove together a tapestry of

heroic tales that had gathered around Gilgamesh into a single action-packed

narrative.

“Oh,

come, dear naiads, tune your lyres and lutes,

And

sing of love with chastest, sweetest notes,

Of

Accad's goddess Ishtar, Queen of Love,

And

Gilgamesh, with softest measure move;

Great

Shamash’s son, of him dear naiads sing!

Of

him whom goddess Ishtar warmly wooed,

Of

him whose breast with virtue was imbued.

He

as a giant towered, lofty grown,

As

Babel’s great princeling was he known,

His

armèd fleet commanded on the seas

And

erstwhile travelled on the foreign leas;

His

mother Ellat-gula on the throne

From

Erech all Kardunia ruled alone.”

à From the Prologue to Ishtar and

Izdubar by Leonidas Le Cenci Hamilton [1884], Slightly Modernized by

the Editor

According to the epic, Gilgamesh was the son of the

mortal human King Lugalbanda and the goddess Ninsumunak. The narrative opens

with the story of how King Gilgamesh met the wildman Enkidu and describes how

the two heroes became steadfast warrior-companions. The poem continues with

exciting battle sequences, in which Gilgamesh and Enkidu destroyed the ogre Humbaba

in the Cedar Forest of Lebanon and slew the Bull of Heaven when it went

rampaging through the streets of Uruk.

The gods were angered by the slaying of the Bull of

Heaven, so they afflicted Enkidu with a fatal illness. Gilgamesh was devastated

by his warrior-companion’s death and set off on a quest to find the secret of

immortality, lest he suffer the same fate as Enkidu. The King of Uruk passed

through many perils as he journeyed to a faraway eastern land, near the gates

of the sunrise. There, Gilgamesh met Siduri (an immortal sage and seer),

Urshanabi (the boatman who ferried Gilgamesh across the Waters of Death), and

finally Utnapishtim (the Mesopotamian equivalent of Noah), who along with his

wife had been granted immortality after the great Flood.

Gilgamesh found and then lost the secret of eternal

youth on his way back home to Uruk, but he returned to his native city a wiser

man. He had discovered – through finding and loss – that true friendship can

change one’s life forever. Gilgamesh had also learned that although death is

unavoidable for mortals, we should celebrate life while it lasts and undertake

heroic deeds to benefit others. At the end of his long reign as King of Uruk,

Gilgamesh died and was buried, and the Divine Council of the gods made him the

Prince of the Otherworld, where he was reunited with his beloved family and

with his warrior-companion Enkidu. As the Prince of the Otherworld, he meted

out justice and mercy to the dead based on the wisdom and understanding that he

had gained during his lifetime on Earth.

Gilgamesh has become a pop culture hero in recent

decades, as his epic story (which was lost for over 2000 years) has now been

translated into several modern languages. Whatever historical truth may lie

behind his legend, Gilgamesh is remembered still today because the leadership

lessons that he exemplified are timeless truths that appear again and again

throughout world literature. Mortality will come to us all, Gilgamesh would

say, but while life lasts, let us spend it in service to others through heroic

deeds and teaching wisdom by example. As the Akkadian epic poets wrote of the

world’s first superhero, some 4000 years ago:

“He

who the heart of all matters has proven, let him teach the nation, He who all

knowledge possesses, therein shall he school all the people, He shall his

wisdom impart and so shall they share it together. Gilgamesh — he was the

Master of wisdom, with knowledge of all things, He it was who discovered the

secret concealed. Aye, he handed down the tradition relating to things

prediluvian, He went on a journey afar, all aweary and worn with his toiling.

He engraved on a tablet of stone all the travail.”

à

Prologue to the Gilgamesh Epic (Slightly Modernized by the Editor

from the 1929 Translation by R. Campbell Thompson)

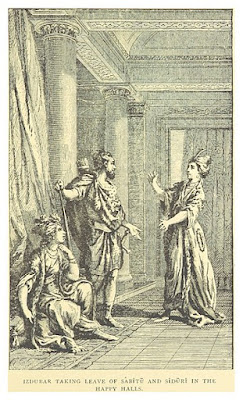

Gilgamesh

(referred to as Izdubar in the above caption) takes leave of Siduri and her

acolyte Sabitu after staying in their “Happy Halls” near the eastern edge of

the known world in Tablet IX of the Gilgamesh Epic. (Image

Credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.